Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms

Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms, or the Pharaonic civilization, was an old civilization in Northeast Africa. It was mainly along the Nile River, in what is now Egypt. Ancient Egyptian civilization started after prehistory, and around 3200 BCE, Upper and Lower Egypt were united under King Menes, also called Narmer. Ancient Egypt was the first organized state in human history.

The history of Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms is divided into stable kingdoms, with periods of instability called the Intermediate Periods: the Old Kingdom in the Early Bronze Age, the Middle Kingdom in the Middle Bronze Age, and the New Kingdom in the Late Bronze Age. Egypt reached its peak during the New Kingdom, controlling Nubia and parts of the Levant, then slowly started to decline. During its history, Egypt was invaded or ruled by foreign powers like the Hyksos, Nubians, Assyrians, Persians, and Alexander the Great. After Alexander died, the Greek Ptolemies ruled Egypt until 30 BCE, when Egypt became a Roman province after Cleopatra.

The Pyramids of Giza are among the most famous symbols of Ancient Egypt. The success of Egypt partly came from the Nile River. Its regular floods and controlled irrigation made the land fertile and produced extra crops, which helped increase the population and support society and culture. The government organized mining, writing, building, farming, trade, and the army. These activities were managed by scribes and religious leaders under the king to ensure cooperation and unity.

The Important achievements of the Ancient Egyptians also include quarrying and building techniques for pyramids, temples and obelisks, mathematics, medicine, irrigation and farming methods, wooden boats, pottery and glass making, the invention of writing, literature and the first known peace treaty with the Hittites. Ancient Egypt left a lasting legacy that influenced the Greeks and Romans, spread around the world and inspired travelers and writers for thousands of years. Discoveries of its monuments in modern times led to the study of Egyptology and more appreciation for its cultural heritage in Egypt and the world.

The history of ancient Egypt is long and complex so historians divide it into clear periods called kingdoms and intermediate periods. This division helps us understand how Egypt developed politically, socially and culturally over time.

Between each kingdom, there were intermediate periods when central power weakened or Egypt faced foreign invasions.

This division makes it easier to follow the history of ancient Egypt and understand how Egyptians maintained unity and developed arts, architecture and science over thousands of years.

Early Dynastic Period of the Ancient Egyptian kingdom(3150 – 2686 BCE)

The Early Dynastic Period includes the First and Second Dynasties, which mark the beginning of written history in Egypt. This period started when King Menes united Upper and Lower Egypt. Thinis, near Abydos (al-‘Araba al-Mafkooda, Belina Center, Sohag Governorate), was the first capital during this period, while Menes also established the northern capital, known as Memphis.

Following this period, the Old Kingdom began with the Third Dynasty, and one of its most famous kings was Djoser (2684 – 2600 BCE), who built the Step Pyramid, the first large stone structure in history.

The Civilization

By around 3600 BCE, the people in Neolithic communities along the Nile relied on farming and animal domestication. Over time, Egyptian society grew and developed toward a full civilization. During this period, a new and distinctive type of pottery appeared, influenced by high-quality pottery from Palestine. Copper began to be widely used. Egyptians also adopted architectural ideas from Mesopotamia, including sun-dried bricks, arches, and decorated walls, which became popular during this time.

The Discoveries

Important archaeological sites from the Archaic Period include the settlement of Ezbet Tel Kafour Najm, about 5 km southwest of Kafr Saqr in the Sharqia Governorate. Excavations by Zagazig University revealed a residential area from the Predynastic period and a cemetery with 127 tombs, most of them intact. These included 60 tombs from the First Dynasty, 23 tombs from the same era, 17 tombs from the Archaic Period, and 13 tombs rich with offerings, including two child burials in pottery vessels, some buried in a crouched position.

Skeletal remains were found in pottery, many marked with the name of King Narmer. Coffins were adorned with jewelry such as stone bracelets and anklets, along with kohl palettes and stone vessels of schist and alabaster, and slate boards for making kohl. Copper vessels, animal bones, and remains of containers with bones and offerings were also discovered. Among the amulets were a green stone scarab, a pierced dark green fly-shaped amulet, a golden ibis bird amulet on one leg, and a carnelian amulet shaped like a winged falcon. Parts of walls from the old residential area were also found, showing remains of ovens and hearths used by the village inhabitants.

Settlements in Canaan and Nubia

Evidence shows that Egyptians began settling in southern Canaan around 3200 BCE, leaving behind fortifications, buildings, pottery, vessels, tools, weapons, seals, and almost every type of artifact. Twenty objects attributed to King Narmer, the first ruler of the Early Dynastic Period, were found in Canaan. There is also evidence of Egyptian presence and settlement in Lower Nubia after the end of the Nubian Culture Group.

The Old Kingdom of the Ancient Egyptian kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period approximately from 2700 to 2200 BCE. It is also called the “Age of the Pyramids” or the “Era of Pyramid Builders” because it includes the reigns of the great kings of the Fourth Dynasty who perfected pyramid construction, like King Sneferu and the rulers Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure who built the pyramids at Giza.

During the Old Kingdom, Egypt reached its first long-lasting peak of civilization marking one of the three “Kingdom” periods (followed by the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom), representing the highest points of Egyptian cultural and political development in the Nile Valley.

The concept of the Old Kingdom as a “golden age” was first proposed in 1845 by the German Egyptologist Baron von Bunsen and its definition has been refined throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The last king of the Early Dynastic Period was closely related to the first kings of the Old Kingdom and the royal capital remained at Ineb-Hedj (Memphis). The main reason for distinguishing the two periods is the major architectural changes and their broad effects on society and economy due to large-scale building projects.

Generally, the Old Kingdom covers the Third Dynasty through the Sixth Dynasty (2686 – 2181 BCE). Most of what we know about the Fourth to Sixth Dynasties comes from monuments and inscriptions which serve as the main historical sources. This period of internal stability and prosperity was followed by a phase of political fragmentation and cultural decline, known as the First Intermediate Period starting with the Seventh Dynasty. Some scholars include the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties as part of the Old Kingdom because central administration continued from Memphis.

During this era, the King of Egypt (not yet called Pharaoh) was considered a living god ruling with absolute power and able to demand the service and resources of his people.

The Rise of the Old Kingdom

The first ruler of the Old Kingdom was Djoser (c. 2691 – 2625 BCE) of the Third Dynasty. He initiated a new building program in Saqqara including the construction of the Step Pyramid, designed by his famous architect Imhotep who pioneered stone construction and the concept of the step pyramid.

At this time, formerly independent regions of Egypt became nomes under royal authority, and local rulers were integrated as governors or tax collectors. Egyptians believed the king to be the earthly embodiment of Horus linking the human and spiritual worlds. Their concept of time was cyclical and the pharaoh ensured the universe remained in balance while the people considered themselves a chosen society.

The Height of the Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom reached its peak during the Fourth Dynasty (2613 – 2494 BCE). King Sneferu, founder of the dynasty, expanded Egypt’s territory from Libya to the Sinai Peninsula and south to Nubia. An Egyptian settlement in Buhen, Nubia, lasted about 200 years.

Sneferu built three pyramids:

- The Meidum Pyramid, abandoned after its outer casing collapsed, The Bent Pyramid at Dahshur then The Red Pyramid at North Dahshur.

He was succeeded by his son Khufu who commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza achieving the fully developed pyramid design. After Khufu, his sons Djedefre and Khafre ruled. Khafre is traditionally credited with the Great Sphinx of Giza, though some evidence suggests Djedefre may have commissioned it as a tribute to his father. Later Fourth Dynasty rulers included Menkaure, builder of the smallest Giza pyramid and Shepseskaf.

The Fifth Dynasty

The Fifth Dynasty (2494 – 2345 BCE) began with Userkaf and is known for the growing importance of sun worship (Ra). Less emphasis was placed on pyramid building while sun temples at Abu Sir became prominent.

Pharaohs like Sahure conducted expeditions to Punt and trade flourished with Lebanon and the Red Sea region. Ships were tied together with ropes rather than nails or metal fasteners. There were also mining and military campaigns in Nubia and Sinai.

The last rulers of this dynasty included Menkauhor Kaiu, Djedkare Isesi and Unas, the first king to inscribe the Pyramid Texts.

The Decline of the Old Kingdom Of Ancient Egyptian Kingdoms

The Sixth Dynasty saw the weakening of pharaonic power with nomarchs gaining independence and hereditary authority. The reign of Pepi II was long, leading to internal disorder and succession struggles.

A severe drought in the 22nd century BCE caused Nile floods to fail, triggering famine. The collapse of centralized power ushered in the First Intermediate Period, a time of political fragmentation, local warlords and social hardship as described in the tomb inscriptions of the nomarch Ankhtifi.

The Art in the Old Kingdom of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

Egyptian art in this period served religious and ideological purposes not mere decoration. The main artistic principles were:

- Frontal view: objects and figures faced the viewer directly.

- Composite view: multiple perspectives were combined for clarity.

- Hierarchy of scale: importance shown by size, the pharaoh or gods were the largest figures.

Human figures had specific proportions: men with broad shoulders and long torsos: women narrower with longer legs. Later, in the Sixth Dynasty, male figures lost muscularity and had larger eyes. Artists used hard stones like gneiss, graywacke and granite with colors carrying symbolic meanings:

- Black = fertility of Nile soil.

- Green = vegetation and rebirth.

- Red = sun and regeneration.

- White = purity.

Sculptures often depicted the king with family or gods, demonstrating youth, vitality and the office of kingship. Statues such as Menkaure with Hathor and Anput showcase these conventions.

The Genetics of the Old Kingdom

A 2025 genetic study sequenced the genome of an Old Kingdom man from Nuwayrat, south of Cairo. Most of his ancestry was North African Neolithic with more than 20% from the eastern Fertile Crescent including Mesopotamia.

This study provides direct evidence of ancient migration from the Fertile Crescent into Egypt, complementing prior archaeological evidence of cultural exchanges, trade and domesticated species transfers. It demonstrates a broad demographic expansion affecting both Anatolia and Egypt during the early dynastic period.

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as the Reunification Period) was the period in ancient Egyptian history that followed the political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from around 2050 to 1710 BCE, spanning from the reunification of Egypt under Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty to the end of the 12th Dynasty. The kings of the 11th Dynasty ruled from Thebes while the kings of the 12th Dynasty ruled from Lisht.

The German Egyptologist Bunsen coined the concept of the “Middle Kingdom” as one of the “three golden ages” in 1845 and the definition of this term evolved significantly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Some scholars also include the entire 13th Dynasty within this period. In that case, the Middle Kingdom lasted until around 1650 BCE while others consider it to end with Merneferre Ay around 1700 BCE, the last king of the Middle Kingdom whose reign is attested in both Upper and Lower Egypt. During the Middle Kingdom, Osiris became the most important deity in ancient Egyptian religion. The Middle Kingdom was followed by the Second Intermediate Period, another time of division that included foreign invasions of Egypt by the Hyksos from West Asia.

The Political History and the Reunification under the 11th Dynasty

After the collapse of the Old Kingdom, Egypt entered a period of weak royal authority and decentralization called the First Intermediate Period. At the end of this period, two rival dynasties, known in Egyptology as the 10th and 11th Dynasties, fought to control the entire country. The Theban 11th Dynasty only ruled southern Egypt, from the First Cataract to the 10th nome of Upper Egypt. In the north, Lower Egypt was ruled by the rival 10th Dynasty from Ihnasia.

Mentuhotep II

Mentuhotep II managed to end the conflict after ascending the throne of Thebes in 2055 BCE. In his 14th year, he took advantage of a rebellion in one of the northern provinces to attack Ihnasia, encountering little resistance. After overthrowing the last ruler of the 10th Dynasty, Mentuhotep began consolidating his authority over all of Egypt, a process that was only completed in his 39th year of reign. For this reason, Mentuhotep II is considered the founder of the Middle Kingdom.

Mentuhotep II led small campaigns south to the Second Cataract in Nubia, which had gained independence during the First Intermediate Period. He also restored Egyptian control over the Sinai region, lost since the end of the Old Kingdom. To strengthen his authority, he revived the ruler cult, portraying himself as a god while ruling wearing the crowns of Amun and Min. He died after a 51 year reign and was succeeded by his son, Mentuhotep III.

Mentuhotep III

Mentuhotep III ruled for only twelve years, continuing to strengthen Theban rule across Egypt and constructing a series of forts in the eastern Delta to protect Egypt from threats from Asia. He also sent the first expedition to the land of Punt in the Middle Kingdom, using ships built in Wadi Hammamat on the Red Sea. Mentuhotep III was succeeded by Mentuhotep IV whose name is notably missing from many king lists. The Turin Papyrus claims that after Mentuhotep III, there were “seven years without kings.” Despite this absence, there is evidence of his reign in a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat, recording expeditions to the Red Sea coast and stone quarries for royal monuments. The leader of this expedition was his vizier Amenemhat, widely believed to be the future king Amenemhat I, the first king of the 12th Dynasty.

The absence of Mentuhotep IV from king lists led to a theory that Amenemhat I seized the throne. While there are no contemporary accounts of this conflict, some circumstantial evidence suggests a civil war at the end of the 11th Dynasty. Inscriptions left by Naheri, a high official of Hermopolis, indicate he was attacked at a place called Shedyet-sha by forces of the ruling king, but his forces were victorious. Khnumhotep I, an official under Amenemhat I, claims to have participated in a convoy of twenty ships sent to pacify Upper Egypt. Donald Redford suggested these events could be evidence of a war between two rivals for the throne. What is certain is that although Amenemhat I came to power, he was not of royal origin.

The 12th Dynasty

From the 12th Dynasty onward, pharaohs often maintained permanent, well-trained armies that included Nubian units. These armies formed the basis for larger forces used to defend against invasions or conduct expeditions up the Nile or across Sinai. However, the Middle Kingdom was primarily defensive in military strategy, establishing fortifications at the First Cataract of the Nile, in the Delta and in Sinai.

The First Intermediate Period of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

The First Intermediate Period in ancient Egyptian history, sometimes called the “dark period,” lasted about 125 years, roughly from 2181 to 2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom. This period includes the Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth and part of the Eleventh Dynasties. The term “First Intermediate Period” was first used in 1926 by Egyptologists Georg Steindorff and Henri Frankfort.

During this time, very few major monuments survived, especially in the early years, because of political and social instability. Egypt was roughly divided between two competing powers: one in Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, near the Faiyum region, and the other in Thebes in Upper Egypt. During this period, temples were believed to be looted, artworks destroyed, and royal statues broken due to the chaos. Eventually, the two kingdoms fought, and the kings of Thebes defeated the kings of the north, reuniting Egypt under a single ruler, Mentuhotep II, in the later part of the Eleventh Dynasty. This event marks the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.

The Events Leading to the First Intermediate Period

The reasons for this period are many. One major reason was the long reign of Pharaoh Pepi II, the last major ruler of the Sixth Dynasty, who ruled from childhood until very old age, possibly over ninety which caused succession problems. The power of local governors, called nomarchs, had grown strong, and their positions became hereditary, making them independent from the king. These local rulers built their own tombs and raised armies which led to conflicts and rivalries between provinces. Another proposed reason was low Nile floods caused by drier climate, which reduced crops and caused famine. However, there is no full agreement among scholars, and some studies suggest the collapse of the state was not directly linked to Nile floods.

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties in Memphis

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties are often overlooked because little is known about them. Manetho, a historian from the Ptolemaic era, mentioned 70 kings who ruled for very short times, symbolizing chaos. The Seventh Dynasty may have been made up of powerful officials from Memphis trying to maintain control after the Sixth Dynasty, and the Eighth Dynasty claimed descent from the Sixth Dynasty and ruled from Memphis. Very few sources survive, but some artifacts exist, like royal scarabs and a small pyramid for King Ibi at Saqqara. Some kings are only mentioned once and their positions in the dynasty are unclear.

The Rise of the Heracleopolitan Kings

After the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties, a group of kings emerged in Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, forming the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties, each with about 19 rulers. These kings are thought to have taken control from the weak Memphis rulers, but archaeological evidence is limited, showing a drastic reduction in the population. The founder of the Ninth Dynasty, Akhthoes or Wahkare Khety I, is described by Manetho as a violent king who caused great harm to the people, went mad, and was eventually killed by a crocodile, though this may be exaggerated. He was followed by Khety II (Meryibre) and then Khety III, who brought some order to the Delta, but their power was much smaller than Old Kingdom pharaohs.

In the south, powerful nomarchs ruled the province of Siut (Asyut), managing canals, taxes, harvests, livestock, the army, and the fleet. This region acted as a buffer between the northern and southern kings and faced attacks from Theban rulers. One famous southern ruler was Ankhtifi, governor of Heracleopolis, who expanded south to Edfu and tried to conquer Thebes but failed. His decorated tomb contains an autobiography describing Egypt’s hunger and poverty, and how he rescued the people, showing that he was the actual ruler and Egypt was no longer united.

The Rise of the Theban Kings

The rise of the Theban kings began around the same time as the Heracleopolitan kingdom. These kings formed the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties and were descendants of Intef, nomarch of Thebes known as the “Keeper of the Door of the South.” Intef organized Upper Egypt into an independent body but did not claim the title of king. His successors did, and Intef II began attacking the north, especially Abydos. By around 2060 BC, Intef II defeated the governor of Nekhen and expanded south to Elephantine. Intef III completed the conquest of Abydos and advanced into Middle Egypt against the Heracleopolitan kings. The first three kings of the Eleventh Dynasty were all named Intef, ending the First Intermediate Period. They were followed by a line of kings called Mentuhotep. Mentuhotep II eventually defeated the Heracleopolitan kings around 2033 BC, reunified Egypt, continued the Eleventh Dynasty, and began the Middle Kingdom.

The Ipuwer Papyrus

During this period, early forms of literature appeared, which later flourished in the Middle Kingdom. A key text is the Ipuwer Papyrus, also called the Lamentations or Admonitions of Ipuwer. Although its exact dating is debated, it refers to the First Intermediate Period, describing the decline of international relations and widespread poverty in Egypt.

Art and Architecture of the First Intermediate Period

Egypt was divided into two main regions, Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. Northern kings kept the Old Kingdom artistic traditions as a symbol of their former glory, while Theban kings developed the “Pre-Unification Theban Style” to show their legitimacy and restore order.

Reliefs in the Pre-Unification Theban style were either raised or sunk, with fine details. Figures had narrow shoulders, high backs, rounded limbs, and fat rolls on males. Women had angular or pointed breasts. Faces had large eyes outlined to show eye paint, flat eyebrows, broad noses, and large oblique ears.

Building projects in the north were limited, with one pyramid for King Merikare at Saqqara and simple private tombs. Wooden coffins were still used but became more decorated, with Coffin Texts inside for the afterlife.

Artworks from Thebes showed new interpretations of traditional scenes with bright colors and altered human proportions. Early Eleventh Dynasty kings built rock-cut tombs called “saff tombs” at El-Tarif with large courtyards and carved rooms for multiple burials. Burial chambers were often undecorated due to the lack of skilled artists.

The Middle Kingdom of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

Early in his reign, Amenemhat I had to campaign in the Delta which had not received the same attention as Upper Egypt during the 11th Dynasty. He also strengthened defenses between Egypt and Asia, ordering walls in the eastern Delta. Possibly in response to this ongoing unrest, Amenemhat built a new capital in northern Egypt called Itjtawy, “Seizer of the Two Lands.” Its exact location is unknown but believed to be near the city’s necropolis in Lisht. Like Mentuhotep II, Amenemhat reinforced his authority through propaganda. The “Prophecy of Neferti” dates to this period, claiming to predict a king, Amenemhat I, rising from southern Egypt to restore the kingdom after centuries of chaos.

Despite this propaganda, Amenemhat never had the absolute power of Old Kingdom pharaohs. During the First Intermediate Period, provincial rulers gained significant power, and their positions became hereditary, with some forming marriage alliances with neighboring provinces. To strengthen his position, Amenemhat ordered land registration, adjusted provincial boundaries, and appointed local governors directly whenever positions became vacant, while tolerating local governance to appease the officials who supported him. This system made the Middle Kingdom more feudal than previous or later periods in Egypt.

In his 20th year, Amenemhat made his son Senusret I co-ruler, beginning a practice repeated throughout the Middle Kingdom and again during the New Kingdom. In his 33rd year, Amenemhat was killed in a conspiracy. Senusret, who was campaigning against the Libyans, rushed to Itjtawy to stop the conspirators. During his reign, Senusret continued direct appointments of local governors, undermining the independence of local priests by building in cult centers across Egypt. His armies extended Egyptian control south to the Second Cataract, built a frontier fortress at Buhen, and annexed Lower Nubia as an Egyptian colony. To the west, he strengthened control over the oases and expanded trade connections to Canaan and Ugarit. In his 43rd year, he appointed Amenemhat II as co-ruler before dying in his 46th year.

The Peak of the Middle Kingdom

Senusret III was a warrior king, often going to battle personally. In his sixth year, he re-dug an Old Kingdom canal around the First Cataract to ease travel to Upper Nubia. Using this project, he launched a series of major campaigns in Nubia in his 6th, 8th, 10th, and 16th years. After victories, he built a series of massive fortresses across the country to create an official border between Egyptian-controlled Nubia and unoccupied Nubia. Guards at these forts were required to report any movements or activities of local populations in the Medjay region, and some of these reports survive, showing how closely Senusret monitored the southern border. The Medjay were not allowed to cross north with boats or travel overland with their herds, but they were permitted to visit local forts for trade. He launched another campaign in his 19th year, but returned due to unusually low Nile levels, which endangered his ships. A soldier’s record also mentions a campaign in Palestine, possibly against Shechem, which is the only known Middle Kingdom military campaign in Palestine.

A rare red carnelian bead found in Egypt is believed to have been imported from the Indus Valley civilization via Mesopotamia, showing Egypt’s international connections. (Tomb 197, Abydos, Late Middle Kingdom. Now in the Petrie Museum, London.)

Domestically, Senusret III is credited with administrative reforms that placed more power in the hands of centrally appointed officials rather than local governors. Egypt was divided into three regions: the North, the South, and “Head of the South” (likely meaning Lower Egypt, most of Upper Egypt, and the Theban provinces during their war with Ihnasia, respectively). Each region had a chief, deputy, and council of officials and scribes. The power of local governors seems to have permanently declined under his rule, interpreted as the central government finally subduing them, although no record directly confirms that Senusret took action against them.

Senusret III left a lasting legacy as a warrior pharaoh. Later Greek historians called him Sesostris, a name later applied to several warrior pharaohs of the New Kingdom. In Nubia, Egyptian settlers worshiped Senusret as a protective god. The length of his reign is debated. His son, Amenemhat III, began ruling after Senusret’s 19th year, considered the last attested year of Senusret III. However, evidence from the 39th year on a temple fragment suggests a possible long co-regency with his son.

The reign of Amenemhat III marked the peak of economic prosperity for the Middle Kingdom. Egypt’s resources were extensively exploited. Mining camps in Sinai, previously used only occasionally, were operated almost continuously, evidenced by the construction of houses, walls, and local tombs. There are 25 separate mentions of mining expeditions in Sinai and four in Wadi Hammamat, one noting more than 2,000 workers. Amenemhat strengthened the southern defenses in Nubia, continued the Fayum irrigation projects, and ruled for 45 years before being succeeded by Amenemhat IV, whose nine-year reign left few traces. By this time, the dynasty’s power was weakening, for several possible reasons. Contemporary records show low Nile floods at the end of Amenemhat III’s reign, likely causing crop failures and destabilizing the dynasty. Additionally, his unusually long reign may have caused succession problems. This may explain the rise of Sobekneferu after Amenemhat IV, the first historically confirmed female pharaoh. She ruled no more than four years, and apparently had no heirs, leading to the abrupt end of the 12th Dynasty and the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom.

The Decline of the Middle Kingdom of the ancient Egyptian kingdom

After Sobekneferu, the throne may have passed to Sobekhotep I. Scholars once believed that Wajef, a former military supervisor, ruled afterward. From this point, Egypt was ruled by a series of kings for about 10–15 years each. Ancient Egyptian sources consider these rulers part of the 13th Dynasty, although the term “dynasty” is misleading because most 13th Dynasty kings were not from a single family. The brief reigns of these kings are attested by few monuments, and the order of succession is only partially known from the Turin Papyrus, which is not entirely reliable.

Following the initial dynastic chaos, a series of longer-reigning kings ruled for about 50–80 years. The strongest rulers of this period included Neferhotep I, who ruled 11 years and maintained effective control over Upper Egypt, Nubia, and the Delta, probably excepting Saka and Avaris. Neferhotep I was also recognized as a ruler of Byblos in present-day Lebanon, indicating that the 13th Dynasty retained much of the power of the 12th Dynasty, at least until the end of his reign.

At some point during the 13th Dynasty, Saka and Avaris began forming autonomous regions: the rulers of Saka became the 14th Dynasty, and the Asian rulers of Avaris became the Hyksos of the 15th Dynasty. According to Manetho, this revolt occurred during the reign of Neferhotep’s successor, Sobekhotep IV, although there is no archaeological evidence to confirm this. Sobekhotep IV was succeeded by Sobekhotep V, followed by Wahibre Ibiau and then Merneferre Ay. Wahibre ruled ten years, and Merneferre Ay ruled 23 years, longer than any other 13th Dynasty king, but left few monuments. Despite this, both appear to have controlled at least parts of Lower Egypt. After Merneferre Ay, no king left evidence outside Upper Egypt. This marked the end of the 13th Dynasty. Southern kings continued to rule Upper Egypt, but Egypt’s unity collapsed, and the Middle Kingdom gave way to the Second Intermediate Period.

The Administration of the Middle Kingdom

When the 11th Dynasty reunified Egypt, they had to create a central administration that had disappeared after the fall of the Old Kingdom. To do this, they appointed officials to positions that had been unused during the decentralized First Intermediate Period. The highest was the vizier, serving as the king’s prime minister, handling all daily government affairs on behalf of the king. This was a huge responsibility, so the role was sometimes split into two: vizier of the North and vizier of the South. It is unclear how often this occurred in the Middle Kingdom, but Senusret I is known to have had two viziers at the same time.

Other positions inherited from Thebes’ regional governance under the 11th Dynasty included the overseer of sealed goods (treasury official) and the overseer of estates (the king’s main agent). These three positions, along with the royal scribe, possibly the king’s personal scribe, were the most important central government posts, as indicated by the number of monuments for those holding them.

Many Old Kingdom positions that had lost their original purpose were revived as honorary roles for the central government. Only high-ranking officials could claim the title “member of the elite.” This basic administrative system continued throughout the Middle Kingdom, although there is evidence of major government reform under Senusret III. Records from his reign show Upper and Lower Egypt divided into separate regions, each governed by its own administrators. Administrative documents and monuments reveal the spread of new bureaucratic titles at this time, suggesting a larger central government. The royal household was made a separate department, and the army was placed under a general. However, some of these titles may have older origins and were simply not recorded on mortuary monuments previously due to religious customs.

The Local Government of the Middle Kingdom

During the First Intermediate Period, Egyptian provinces were controlled by powerful families with titles like “Great Governor” or “Great Chief.” This position evolved during the 5th and 6th Dynasties when one individual exercised various authorities over regional officials. At the same time, regional aristocrats built elaborate tombs, demonstrating their wealth and power. By the end of the First Intermediate Period, some provincial rulers acted as kings, like Naheri of Hermopolis, who dated inscriptions according to his royal years.

When the 11th Dynasty came to power, it was necessary to subdue local governors for a unified central government. Major steps to achieve this began under Amenemhat I. He made the city the center of administration, not the province, and only governors of major cities could hold the title “Great Chief.” This title continued until Senusret III, and the complex tombs indicating their power also continued before suddenly disappearing. This has been interpreted in several ways. Traditionally, it was thought Senusret III suppressed these ruling families. More recently, alternative explanations suggest that Senusret II educated the sons of provincial rulers in the capital and appointed them to government positions, potentially preventing local families from producing heirs to govern. While the title of “Great Overseer of the Province” disappeared, other distinctive titles remained. During the First Intermediate Period, officials holding the title often also held the title of overseer of priests. In the late Middle Kingdom, some families held both the title of mayor and overseer of priests as hereditary offices. Therefore, some argue that major regional families were never fully subdued but integrated into the central administration. While large tombs of provincial rulers disappear at the end of the 12th Dynasty, royal monuments also soon vanish due to the general instability surrounding the decline of the Middle Kingdom.

The Agriculture and Climate of the Middle Kingdom

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, annual Nile floods were essential to fertilize surrounding lands, crucial for agriculture and food production. Evidence suggests that the collapse of the Old Kingdom may have been partly due to lower Nile floods, causing famine. This trend reversed during the early Middle Kingdom, with relatively high Nile levels recorded for much of the period, averaging 19 meters above pre-flood levels. Years of repeated high floods correspond to the most prosperous times of the Middle Kingdom, especially under Amenemhat III, as confirmed in contemporary literature like the Instructions of Amenemhat, which describe flourishing agriculture.

The Art of the Middle Kingdom of the ancient egyptian kingdom

After Egypt was reunified in the Middle Kingdom, the kings of the 11th and 12th Dynasties could focus on art. In the 11th Dynasty, royal artworks were influenced by the old style from the 5th Dynasty and early 6th Dynasty. During this time, the pre-unification Theban style disappeared. These changes had an ideological purpose: the 11th Dynasty kings wanted to create a centralized state after the First Intermediate Period and return to the political ideals of the Old Kingdom.

In the early 12th Dynasty, art became more uniform due to royal workshops’ influence. At this time, elite artworks reached very high quality, unmatched before or after. Egypt flourished in the late 12th Dynasty, reflected in the quality of materials used for both royal and private monuments.

Royal tombs of the 12th Dynasty were pyramid complexes similar to those of the 5th and 6th Dynasties. In the Old Kingdom, these were made from stone blocks, but Middle Kingdom kings used mudbrick cores with limestone casing. Private tombs, such as in Thebes, usually had a long corridor ending in a small chamber, often with little or no decoration.

Stone coffins had flat lids, continuing Old Kingdom traditions, but decorations were more varied and of higher artistic quality than any coffins made before or after. Funerary paintings also developed, adding the deceased’s wife and family members to the traditional image of the deceased sitting before offerings.

By the late Middle Kingdom, artistic objects in non-royal tombs changed. Wooden model tombs became less common and were replaced with small pottery models. Magical rods, sticks, animal figurines, and fertility symbols were buried with the dead. Funerary statues and monuments increased, but their quality decreased. Coffins with interior decorations became rare, while exterior decorations became more detailed. Feather coffins first appeared at this time, made of wood or cartonnage shaped like a wrapped body with a linen covering and funerary mask.

Excavations at Abydos uncovered over 2,000 private paintings, ranging from excellent to basic, though few belonged to the elite. Classic royal boundary paintings also appeared for the first time, often with rounded tops. Senusret III used these to mark Egypt’s borders with Nubia. The flourishing of this period allowed lower elites to commission statues and paintings, though with lower artistic quality. Non-royal paintings aimed to ensure eternal existence.

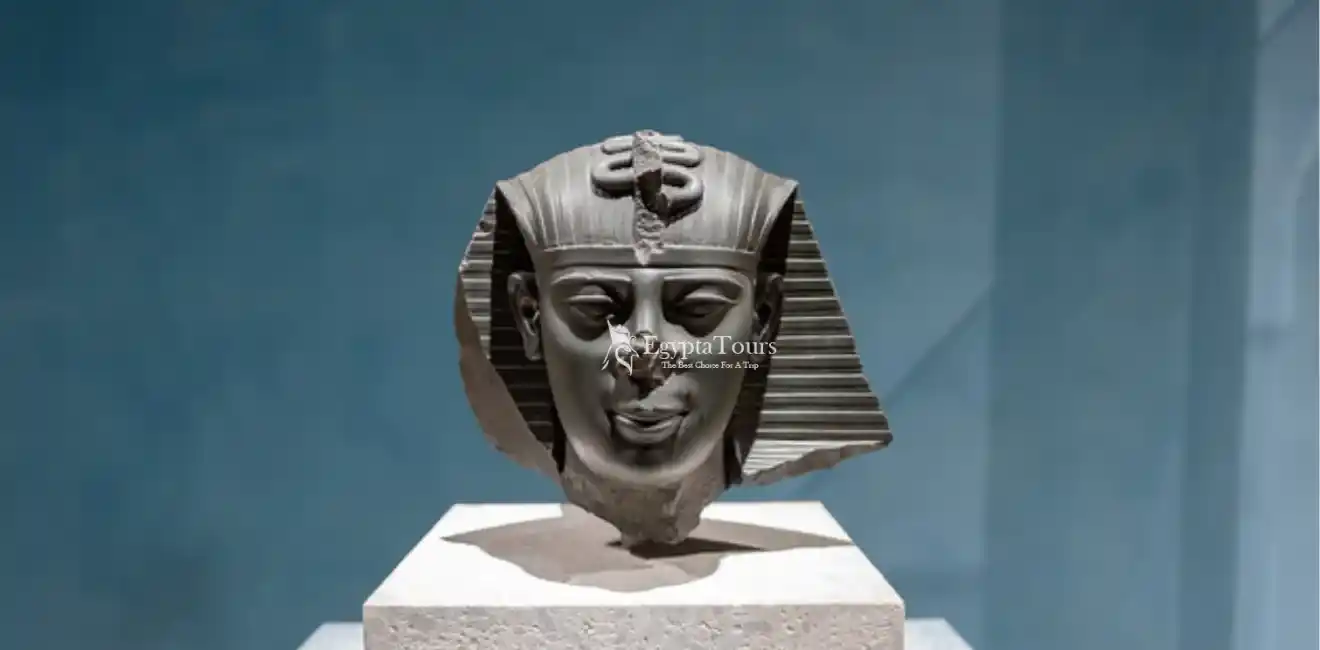

Statues and Proportions of the Middle Kingdom

In the first half of the 12th Dynasty, human proportions returned to the traditional Memphis style of the 5th and early 6th Dynasties. Male figures had broad shoulders and thick muscular limbs, while females had slender bodies with little muscle.

A new grid system was introduced to guide statue and relief production. This system allowed more body parts to be distinguished. Standing figures used 18 squares from feet to hairline; seated figures used 14 squares from feet to hairline, accounting for horizontal thighs and knees.

The black granite statue of King Amenemhat III is an example of this proportional system, showing the balanced and idealized male form. Most royal statues, like this one, symbolized the king’s power.

Egyptian statues reached their artistic peak during the Middle Kingdom. Royal statues combined elegance and power in a way rarely seen afterward. One popular form was the sphinx, which appeared in pairs with human faces, a lion’s mane, and ears. An example is the diorite sphinx of Senusret III.

The Literature of the Middle Kingdom

Richard B. Parkinson and Ludwig D. Morenz explained that ancient Egyptian literature, carefully defined as “fine literature” was not written until the early 12th Dynasty. Old Kingdom texts were mainly for preserving deities, ensuring the afterlife and recording practical accounts. Writing for entertainment or intellectual curiosity appeared in the Middle Kingdom.

Parkinson and Morenz also suggest that Middle Kingdom writings were often copies of older oral literature. Some popular folk poetry was preserved in later writings.

The growth of the middle class and the increasing number of scribes required for an expanded bureaucracy under Senusret II helped stimulate Middle Kingdom literature. Later Egyptians considered Middle Kingdom literature “classical.” Stories like The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and The Story of Sinuhe were composed during this period and widely copied afterward. Many philosophical works were also created, including dialogues between a man and his soul and the Teachings of Dua-Kheti, which praised the writer’s role above all other professions. Magical tales were also written, like stories about Pharaoh Khufu in the Westcar Papyrus.

Kings from the 12th Dynasty to the 18th Dynasty helped preserve some of the most important Egyptian papyri.

The Second Intermediate Period of the ancient Egyptian kingdom

The Second Intermediate Period in ancient Egypt lasted from about 1782 to 1550 BC. During this time, Egypt was divided into smaller kingdoms for the second time. This happened after the end of the Middle Kingdom and before the start of the New Kingdom. Usually, this period includes the 13th dynasty up to the 17th dynasty, but historians and Egyptologists do not completely agree on its exact limits.

This period is best known for the Hyksos, a people from West Asia, who set up the 15th dynasty and ruled from their capital, Avaris. According to the ancient historian Manetho in his book Aegyptiaca, Avaris was founded by a king named Salitis. The Hyksos may have settled in Egypt peacefully at first but later stories describe them as violent conquerors who oppressed the Egyptians.

The main source for understanding the kings and political history of the Second Intermediate Period is the Turin King List, which was made during the time of Pharaoh Ramesses II. Another important source is the study of scarabs, small beetle-shaped amulets made in large numbers in ancient Egypt, often with the names of kings written on them.

The Collapse of the Middle Kingdom

The 12th dynasty of Egypt ended in the late 19th century BC when Queen Sobekneferu died. She had no children to inherit the throne. With her death, the Middle Kingdom’s most prosperous era came to an end. She was followed by the 13th dynasty, which was weaker.

The Byzantine historian George Syncellus wrote that all three sources of the king lists, Africanus, Eusebius, and the Armenian version of Eusebius, say that the 13th dynasty had sixty kings who ruled for about 453 years. The 13th dynasty continued to rule from the capital of the 12th dynasty, called Itjtawy, meaning “Seizer of the Two Lands,” for most of its history.

The only pyramid completed during the 13th dynasty was the pyramid of Pharaoh Khendjer.

Migration to Thebes

The 13th dynasty later moved its capital to Thebes in Upper Egypt, possibly during the reign of Merneferre Ay. Scholar Daphna Ben Tor believes this move happened because the eastern Delta and Memphis region were invaded by Canaanite rulers, who had their own culture, similar to the late Palestinian Middle Bronze Age culture. Some historians see this move as marking the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the Second Intermediate Period.

However, Ryholt and Baker disagree. They point to the stele of Seheqenre Sankhptahi, who ruled toward the end of the dynasty, showing that he had control over Memphis.

Even though the 13th dynasty may have controlled Upper Egypt, the 14th dynasty ruled the Delta in Lower Egypt. Both dynasties agreed to coexist, allowing trade between them. The rulers often changed quickly, probably because of difficulties keeping power and possibly due to famine. This made it easier for smaller dynasties to take over parts of Egypt.

The Second Intermediate Period of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

Like the First Intermediate Period, the Second Intermediate Period was a time of division. Egypt was ruled by rival centers of power: one in Upper Egypt (Thebes) and one in Lower Egypt (the Delta). Each controlled part of the country.

The 14th Dynasty

The 13th dynasty could not keep control over all of Egypt. A local ruling family in the Delta broke away and formed the 14th dynasty (around 1700–1650 BC). According to Syncellus, the 14th dynasty had 76 kings and their court was in Xois, today called Sakha. Different sources give different lengths of reign. Africanus said the dynasty ruled for 184 years, and the Armenian version of Eusebius said 484 years.

The exact borders of the 14th dynasty are unclear because few monuments remain. Scholar Kim Ryholt believes that the 14th dynasty controlled most of the Delta, from Athribis in the west to Bubastis in the east. Many Egyptologists today think that Avaris, not Xois, was the real capital.

The first five rulers of the 14th dynasty may have been Canaanite or Semitic, based on their names, although some scholars disagree. The most well-known ruler is Nehesy Aasehre, who left his name on two monuments in Avaris. He was the son of King Sheshi and a Nubian queen named Tati.

The early years of the 14th dynasty were successful, but like the late 13th dynasty, the kings were replaced quickly. Eventually, the Hyksos overthrew the 14th dynasty.

The 15th Dynasty “The Hyksos”

The Hyksos formed the 15th dynasty (around 1650–1550 BC). The first king, Salitis, is described by Africanus as a “shepherd king.” He settled in the Delta and made Avaris his capital. Manetho says he conquered all of Egypt, but it is more likely he only controlled Lower Egypt. Salitis might be the same person as Sharek or Sheshi, the best-known king of this period.

According to the Turin King List, there were six Hyksos kings, ending with Khamudi. The 15th dynasty ruled from Avaris but did not control all of Egypt. Some parts of northern Upper Egypt remained under the Abydos dynasty and the early 16th dynasty.

Kings of the 15th Dynasty:

- Salitis: first king, mentioned by Manetho, ruled 19 years.

- Semqen: early Hyksos king, mentioned in the Turin King List.

- Aperanat: another early Hyksos king.

- Khyan: ruled for 10+ years.

- Yanassi: Khyan’s eldest son, maybe mentioned as King Iannas by Manetho.

- Sakir-Har: known from a doorjamb at Avaris.

- Apophis: ruled around 1590–1550 BC for 40+ years.

- Khamudi: last king, ruled 1550–1540 BC.

It is debated whether the Hyksos came by military invasion or by migration. Modern studies using strontium isotope analysis suggest that it was a peaceful migration, mostly of women, rather than a violent conquest.

The Abydos Dynasty

The Abydos dynasty (around 1640–1620 BC) may have been a small local dynasty in Upper Egypt, contemporary with the 15th and 16th dynasties. It probably ruled only Abydos or Thinis. Very little is known, and most of its kings are only mentioned in the Turin King List: Wepwawetemsaf, Pantjeny, Snaaib and Senebkay. The dynasty ended when the Hyksos expanded into Upper Egypt.

The 16th Dynasty

The 16th dynasty (around 1650–1580 BC) ruled the Theban region in Upper Egypt. According to the more reliable version of Manetho (Africanus), this dynasty included “shepherd kings” like the Hyksos, but Eusebius called them Theban rulers.

Their main concern was the war with the 15th dynasty. The Hyksos armies gradually captured towns from them and eventually threatened Thebes. Famine also affected Upper Egypt during this period. Around 1580 BC, the 16th dynasty was defeated by King Khyan of the Hyksos 15th dynasty.

The 17th Dynasty

The 17th dynasty (around 1571–1540 BC) was established by the Thebans after the fall of the 16th dynasty. Details about how they expelled the Hyksos from Thebes are unclear. Some sources suggest that the 16th dynasty included both Hyksos rulers and Theban rulers.

The 17th dynasty saw four different ruling families, and the last king did not have a male heir. Powerful families then ruled for short periods. The dynasty kept a short peace with the 15th dynasty. Seqenenre (c. 1549–1545 BC) began a war against the Hyksos. His brother, Kamose (c. 1545–1540 BC), continued the war, and Ahmose I eventually defeated the Hyksos completely, becoming the first king of the 18th dynasty and the New Kingdom.

Reunification and the Start of the New Kingdom

At the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the 18th dynasty came to power. King Ahmose I finished expelling the Hyksos and reunited Egypt, bringing both Upper and Lower Egypt under his rule. This marked the start of the New Kingdom, a period of great wealth, power, and stability.

The New Kingdom of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

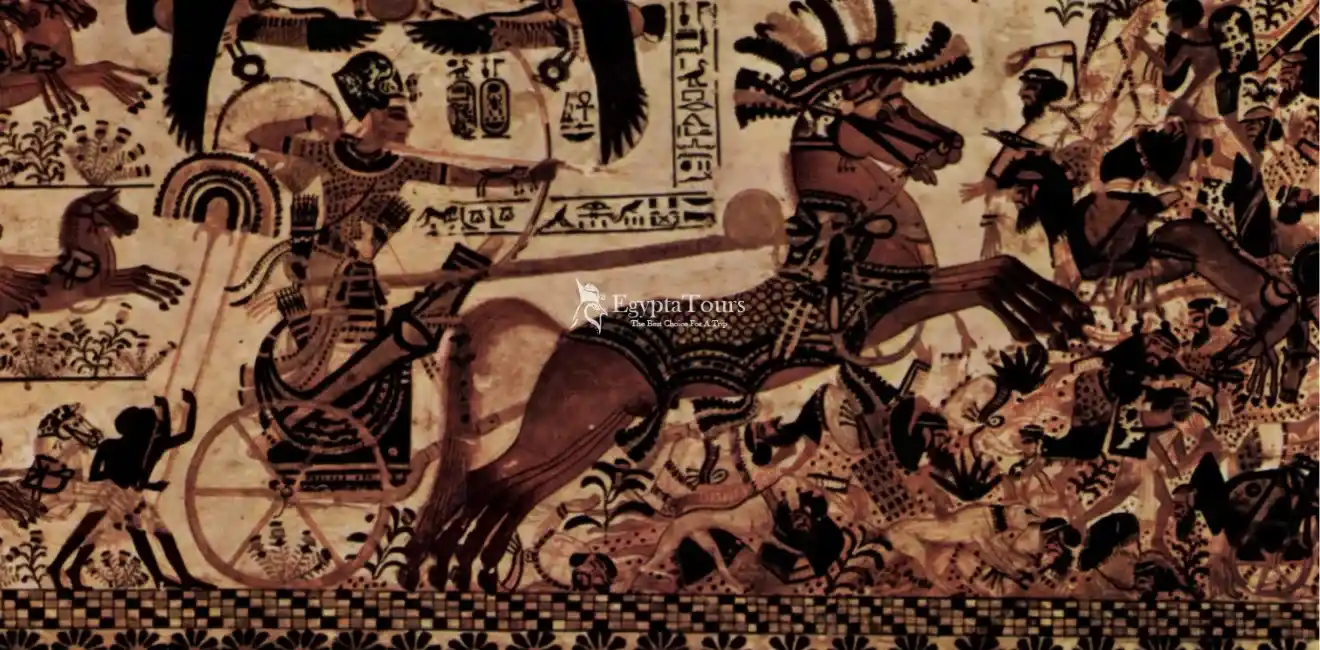

The New Kingdom, also called the Modern State, is known as the “Age of Military Glory.” It lasted roughly from the 16th century BCE to the 11th century BCE, covering the 18th, 19th, and 20th Egyptian dynasties. Carbon dating shows that the New Kingdom began around 1570–1544 BCE. It followed the Second Intermediate Period and marked the peak of Egypt’s political, military and economic power.

The term “New Kingdom of Egypt” was coined by German Egyptologist Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen, who considered it one of Egypt’s golden ages. The later part of the New Kingdom, under the 19th and 20th Dynasties, is known as the Ramesside Period, named after the kings who took the name Ramses, beginning with Ramses I, the founder of the 19th Dynasty. After the Hyksos rule, Egypt built natural defenses against invasions from the Levant, and during this period, Egypt reached its maximum territorial expansion both north and south.

Rise of the New Kingdom

Egypt reached its maximum empire around 1450 BCE. The 18th Dynasty included famous rulers such as Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and Tutankhamun. Hatshepsut focused on foreign trade, including an expedition to Punt which brought wealth and prosperity to Egypt.

Ahmose I is considered the founder of the 18th Dynasty. He completed his father’s campaigns against the Hyksos and reunited Egypt. Around his tenth year, he began expelling the Hyksos from the Nile Delta, destroyed their stronghold at Avaris, pushed them beyond the eastern border and besieged Sharuhen in Palestine. His officers and soldiers were rewarded with loot and captives creating a strong military class. Ahmose expanded south to Nubia and created the position of Viceroy of Kush to manage the territories directly under the king.

The 18th Dynasty

Amenhotep I

Amenhotep I extended Egypt’s borders south to the Third Cataract, collected tribute from Asian territories and built major temples for the gods, especially Amun Ra. Royal tombs shifted from pyramids to rock cut tombs, starting the idea of the Valley of the Kings with mortuary temples on desert edges.

Thutmose I

Thutmose I continued southward expansion in Nubia, reaching the Fourth Cataract and setting new boundaries near the Fifth Cataract. Goals included access to gold and protection from Kush. He also expanded Egyptian influence in Syria, renewed Karnak Temple, built walls, towers and obelisks and forced Syrian princes to pledge loyalty.

Thutmose II

Thutmose II continued the rule of his rule, suppressed rebellions in Nubia, built smaller mortuary temples in West Thebes and continued decorating the royal palace.

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut, daughter of Thutmose I and wife of Thutmose II, ruled alongside her stepson Thutmose III and later on her own. She controlled key positions through loyal officials including Senenmut, overseer of royal works. Her policies were mainly trade oriented rather than military. She led a successful expedition to Punt, restored trade disrupted during the Hyksos occupation, and brought back gold, ebony, animal skins, baboons, incense and live trees. She built her mortuary temple at Deir el Bahari and was buried in the Valley of the Kings beside her father.

After Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose III became ruler and faced rebellions in Megiddo, Syria and Palestine. He defeated rebellious Palestinian cities, personally led the siege of Megiddo and enforced loyalty of regional princes bringing some to Egypt for education in governance.

He conducted multiple campaigns in Asia capturing cities from eastern Anatolia to Punt and extended Egypt’s control from Libya to the Euphrates. He is sometimes called “Napoleon of Egypt” completing at least 16 campaigns in 20 years.

Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV

Amenhotep II joined the rule before his father’s death, assisted in campaigns in Syria, ensured city loyalties and built temples in Thebes and Nubia.

Thutmose IV conducted military tours in Syria and Palestine, suppressed minor rebellions, negotiated peace with Mitanni through marriage and built a large obelisk in West Thebes and small temples.

Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III became king around age 12 and married Queen Ti. He focused on massive temple construction in Thebes and Luxor, led Nubian campaigns for gold and resources and maintained peaceful relations with Asia through marriage and tribute. Military officers gained top administrative roles with the most prominent being Amenhotep, son of Hapu who acted as advisor and intermediary to the king.

Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten)

Amenhotep IV, later Akhenaten, changed his name to show devotion to Aten focusing on the worship of the sun alone. He founded Akhetaten (modern Amarna) with temples, palaces and officials’ tombs. His religious and cultural reforms changed art, language and administration, though Egypt lost some control in Syria.

Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb and Ramses I

Tutankhamun restored Amun worship and moved the capital to Memphis, continuing construction and dying young. He was succeeded by Ay then Horemheb who reformed the state, army, police and courts. Horemheb died without heirs and his minister Pa Ramessu became king as Ramses I, founder of the 19th Dynasty.

By the end of the 18th Dynasty, the Hittites expanded into Phoenicia and Canaan, becoming a major power that Seti I and Ramses II would face in the 19th Dynasty.

Peak of the New Kingdom of the ancient egyptian kingdom

The Nineteenth Dynasty

The Nineteenth Dynasty was founded by Vizier Ramesses I who was chosen by Pharaoh Horemheb the last ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty as his successor. Ramesses I came from a non-royal military family in the eastern Nile Delta. His rise marked a political shift toward the Delta. His reign was short and transitional between Horemheb and the powerful kings of the dynasty. In 1292 BCE, Ramesses I became pharaoh and shortly after appointed his son Seti I as co-ruler to help manage royal duties.

While Seti I planned campaigns in Syria to regain lost Egyptian territories, Ramesses I completed the decoration of the second pylon and its entrance at the Karnak Temple in Thebes, dedicated to the national god Amun, partially started by his predecessor. He also contributed to the Great Hypostyle Hall in Karnak, beginning its decorations shortly before his death in 1290 BCE. Inscriptions show he ruled about 1 year and 4 months. He was buried in a small hastily prepared tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Later, during political unrest, his mummy was moved to a secret location. In the 19th century, the tomb was rediscovered, but the remains were stolen and displayed in a small museum near Niagara Falls, Canada, then later transferred to the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, and finally returned to Egypt in 2003.

Seti I was a successful military leader who restored Egypt’s authority in western Asia. He defeated Mitanni and dealt with the Hittites, securing the coastal cities and battling King Muwatalli to regain Qadesh. Despite his victories, Egypt’s control over northern Syria was temporary. He signed a peace treaty with the Hittites, securing the border at the Orontes River and defeated Libyans trying to invade the Delta. Seti I also led a southern campaign, possibly to the Fifth Cataract of the Nile.

Seti I’s reign was a period of prosperity. He restored many monuments damaged during the Amarna period, fortified borders, reopened mines and quarries, dug wells, and rebuilt collapsed temples and shrines. He continued the construction of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, a masterpiece of Egyptian architecture, and commissioned detailed reliefs depicting his campaigns. Many scholars consider Seti I the greatest king of the Nineteenth Dynasty, even more than his famous son Ramesses II.

Ramesses II

Before Seti I’s death, he named his son Ramesses II as crown prince. During Ramesses II’s long reign, he built massive religious monuments across Egypt and Nubia and established a new capital, Pi-Ramesses, in the eastern Delta. His cartouches were inscribed everywhere, often over older monuments. Although he liked to depict himself as a great warrior in temple reliefs, his actual military campaigns were few. The most famous was the Battle of Qadesh in his fifth year, followed by a peace treaty with the Hittites.

Ramesses II constructed monumental works, including the Abu Simbel temples and his funerary temple, the Ramesseum. He completed Seti I’s temple at Abydos and developed Pi-Ramesses. He used art to glorify his victories and placed colossal statues of himself, more than any other pharaoh. Most of his building projects began early in his reign: towards the end, Egypt’s economy declined.

His chief queen was Nefertari who died early and other queens included Isetnofret and Mertamun. He had over 100 children. His mummy shows an elderly man with a narrow face, prominent nose and strong jaw. Ramesses II’s reign represents the height of Egypt’s imperial power, maintaining control over Palestine and neighboring regions until the end of the Twentieth Dynasty.

Merenptah

Merenptah, the thirteenth son of Ramesses II, succeeded him. In his inscriptions, he described a Libyan invasion in his fifth year, supported by the Sea Peoples. He defeated them and maintained Egypt’s territories. He also sent grain and military support to the Hittites respecting the previous peace treaty.

Seti II and Siptah

After Merenptah’s death, rival factions in the royal family fought for the throne. Seti II (1204–1198 BCE) took power, facing a usurper named Amenmesse and a Nubian revolt. He was succeeded by Siptah whose reign was supported by the queen mother, Twosret. This period experienced temporary instability before Setnakhte, founder of the Twentieth Dynasty, restored order.

Later Years of Power: Twentieth Dynasty

Setnakhte established the Twentieth Dynasty and restored order. His son, Ramesses III, was the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom. His achievements are hard to assess because he copied much of Ramesses II’s works, especially in his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu. However, he fought decisive battles against Libyans and the Sea Peoples and even used some of them as mercenaries. He promoted trade, industry and mining in Sinai and Nubia.

During his later years, administrative difficulties and worker strikes emerged. One of his secondary wives plotted to assassinate him to put her son on the throne. A special court of twelve judges tried the conspirators, executing them. In 2012, CT scans revealed a deep throat wound in his mummy, showing he was indeed killed. He died in his 32nd year and Ramesses IV succeeded him.

Priestly Families

During the Ramesside period, major priestly families gained power, controlling wealth and administration, especially in Thebes. Lower Egypt sources are scarce. Ramesses V, VI, VII, VIII, IX and X faced economic difficulties, rising grain prices and tomb robberies. By the reign of Ramesses XI, the authority of priests increased further, society became more religiously centered and Egypt eventually split into two separate dynasties.

Cultural and Religious Changes

Religious devotion grew in this period. Private tombs shifted from secular to religious scenes. Texts emphasized fate and divine will, showing Egyptians adapting to a more localized, temple focused society rather than a centralized royal system.

Thebes: The Center of Civilization

During the New Kingdom, Egypt enjoyed unprecedented wealth, prosperity and glory. The city of Thebes became the center of human civilization and the capital of the world. Under Thutmose III, Thebes reached its peak, adorned with magnificent temples, shrines, obelisks, and statues. Pharaoh Horemheb focused on issuing laws to regulate the relationship between individuals and the ruling authority.

The art of the New Kingdom

The art of the New Kingdom (1550–1077 BCE) corresponds to the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties. Egypt reached the peak of artistic achievement during this era. After this long period of influence in the Third Intermediate Period, later times would lack the resources for such artistic accomplishments. This period also marks a clear break from the instability seen in the Second Intermediate Period.

This was the great era of funerary architecture after the age of the pyramids. In the Valley of the Kings, massive tombs were carved into the mountainside. Some, like the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut and her tomb at Deir el-Bahari, bent gracefully into the rock face resembling gigantic pyramids.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s treasure amazed the world with its wealth of gold, precious stones, and extraordinary craftsmanship. Many sculptures from the New Kingdom capture a stunning naturalism, showing lifelike faces and bodies. However, during Akhenaten’s reign, figures were reshaped in a unique and sometimes strange style. Even the famous bust of Nefertiti reflects this experimental art. Modern research allows scholars to study these works in detail and propose increasingly accurate hypotheses about their design and realism.

Relief art and other Egyptian artistic forms remained very “Egyptian” with distinctive features like frontal eyes and profile faces. Yet, this period also brought surprises. Some tomb paintings like those in Thutmose III’s tomb, depict people in a controlled gesture style without reference to scale. Artists also produced smaller sketches on limestone or pottery fragments (ostraca), often whimsical or illustrative of stories and myths.

Architecture of the Egyptian Empire

Near the end of the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BCE), the rulers of Thebes (Seventeenth Dynasty) expelled the Hyksos kings from the Delta. Ahmose I reunited Egypt, beginning the New Kingdom, the third great era of Egyptian culture. The pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty expanded Egypt’s influence into the Near East and secured complete control over Nubia up to the Fourth Cataract. This brought immense wealth, much of which was offered to the gods, especially Amun Ra, in temples like Karnak, expanded over generations.

Even though Nineteenth Dynasty rulers built administrative capitals near their residences, Thebes remained the religious and cultural heart. Pharaohs built their mortuary temples and were buried in massive rock-cut tombs, decorated with texts about the afterlife. Deir el-Medina housed the artisans who built these tombs, leaving extensive records of daily life and craft in ancient Egypt.

The New Kingdom is famous for its monumental architecture and statues honoring gods and pharaohs. Over nearly 500 years of political stability and economic prosperity, artists produced abundant works, including funerary art for non-royals, sculptures in Deir el-Medina and quick sketches on pottery or limestone shards (ostraca).

Royal tombs were lavish, with mortuary temples on desert edges dedicated to the deceased ruler and Amun. Burials took place deep underground in the Valley of the Kings, with the only above-ground symbol often being the natural “pyramid” atop the mountain. The nearly intact tomb of Tutankhamun (1335–1325 BCE) shows the wealth of Egyptian kings and the skill of their artisans.

Many temples were also expanded during this period. Karnak existed as a religious site before the Eighteenth Dynasty. Hatshepsut built her mortuary temple in the first half of the dynasty and Thutmose III continued decorations, including the star-covered ceilings. Seti I’s additions created the massive Hypostyle Hall with 134 decorated columns. This wealth came largely from royal lands and offerings.

During Thutmose III’s reign, the powerful state gave enormous wealth to Amun’s priests, who became increasingly autonomous. Later pharaohs gradually distanced themselves from the priests, especially under Akhenaten who introduced radically different artistic styles. Eventually, the Ramesside pharaohs moved the capital to the Delta (Pi-Ramesses) for political and religious reasons, reducing priestly influence in Thebes.

Instead of pyramids, New Kingdom pharaohs were buried in rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile. These tombs, along with temples and monuments, made Thebes one of Egypt’s most famous architectural complexes: Karnak, mortuary temples and “Temples of Millions of Years” including Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahari.

In tomb art, artists gradually shifted from daily life scenes to religious depictions, especially under Ramesses II. Deir el-Medina preserved vivid paintings with highly skilled depictions of couples, gods and rituals. Hatshepsut’s temple also records trade with Africa, including expeditions to Punt, bringing back incense, ivory and exotic animals.

Luxor Temple

The Luxor Temple, on the east bank of the Nile, began under Amenhotep III in the 14th century BCE. Later pharaohs, including Horemheb, Tutankhamun, and Ramesses II, added statues, columns, and decorations. Ramesses II’s massive pylon depicts military victories, especially the Battle of Qadesh. Two granite obelisks were erected; one remains in Luxor, the other was moved to Paris in 1835. The temple includes open courtyards, columned halls, and inner sanctuaries, often decorated with festival scenes and colors.

Malqata Temple

During Amenhotep III’s reign, over 250 buildings and monuments were built, including the Malqata complex, serving as his royal palace. Covering around 226,000 m², it included residences, courts, gardens, and a temple. The central palace had banquet halls, throne rooms, storage, and living quarters. The temple was divided into central, northern, and southern sections, with rooms for worship, including dedication to Ma’at, and was decorated with glazed tiles, painted walls, and star-covered ceilings.

Important Pharaohs of the New Kingdom

- Ahmose I: Expelled the Hyksos, founded the New Kingdom and controlled Nubia.

- Thutmose I: One of the greatest kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

- Hatshepsut: Built her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, sent trade expeditions to Punt, Nubia and Phoenicia.

- Thutmose III: A brilliant military and administrative leader: expanded Egypt’s empire to Punt, Palestine and Syria: pioneered surprise attacks and brought foreign princes to Egypt for education.

- Akhenaten: Introduced monotheism worshipping Aten, neglected state affairs and caused corruption.

- Tutankhamun: Famous for his intact tomb: restored Thebes as the capital and revived the cult of Amun.

Horemheb: Ended religious unrest and restored order after Akhenaten. - Ramesses II: Famous Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh; rebuilt Egypt, fought the Hittites at Qadesh, and signed one of the first recorded peace treaties.

- Ramesses III: Defended Egypt from Mediterranean invaders and Libyans: maintained the empire’s safety.

Sudan in the New Kingdom

During the Middle and New Kingdoms, Egypt controlled part of Sudan (ancient Kush) making Egyptian the official language. Ahmose and Thutmose I expanded Egyptian influence to the Fourth Cataract. Egyptian rule lasted six centuries, during which Sudanese adopted Egyptian religion and culture. Pharaohs appointed governors to manage Sudan, exploiting resources like gold, ebony, ivory, incense, exotic animals and livestock. After contact ended, Egyptian language knowledge declined, and Kushite culture developed its own script at Meroë, which was the capital from the 6th century BCE to the 4th century CE. Egypt’s civilization deeply influenced Sudanese culture and trade.

The End of the New Kingdom of the ancient egyptian kingdom

The pharaoh’s power weakened over time, facing repeated raids from Libyans and Mediterranean peoples. Ramesses III successfully repelled these invasions. Eventually, pharaoh authority faded entirely and the Amun priesthood gained control with the high priest even taking the throne during the Third Intermediate Period.

The Third Intermediate Period of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom

The Third Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt started when Pharaoh Ramesses XI died in 1077 BC. His death ended the New Kingdom. After that, the Late Period began. There are different opinions about the start of the Late Period, but most historians agree it began when the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty was founded by Pharaoh Psamtik I in 664 BC. This happened after the Nubian Kushite rulers of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty left Egypt. They were driven out by Ashurbanipal, the king of Assyria.

The term “Third Intermediate Period” became widely used in 1978 by British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen, when he used it as the title of his book about this period. Kitchen said that the period was not as chaotic as some think, and he preferred to call it the “Post-Imperial Epoch,” but using the term in his book made it very popular among scholars.

This period was ruled by non-Egyptians and is considered a time of political weakness and division in the country. It happened at the same time as the collapse of civilizations in the Late Bronze Age in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, including the Greek Dark Ages.

History of the Third Intermediate Period

Twenty-First Dynasty

The Twenty-First Dynasty was marked by divided rule in Egypt. Even during Ramesses XI’s reign, the Twentieth Dynasty was losing control of Thebes and the priests there were gaining more power. After Ramesses XI died, Smendes I became king, ruling mainly from Tanis in Lower Egypt. Meanwhile, the High Priests of Amun in Thebes controlled Middle and Upper Egypt in practice, though they were not called pharaohs. However, this division was not very serious because the priests and the pharaoh belonged to the same family.

Twenty-Second and Twenty-Third Dynasties

The Twenty-Second Dynasty reunited Egypt under Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC). He came from a family of Libyan immigrants called Meshwesh. This brought stability for more than a century.

After Osorkon II’s reign, Egypt split again into two states: Shoshenq III ruled Lower Egypt from 818 BC while Takelot II and his son Osorkon III ruled Middle and Upper Egypt.

In Thebes, a civil war broke out between Pedubast I, who declared himself pharaoh, and Takelot II/Osorkon B. The conflict lasted for many years until year 39 of Shoshenq III, when Osorkon B defeated his enemies. He then established the Upper Egyptian Twenty-Third Dynasty. After Rudamun’s death, the kingdom broke apart, and small local kings ruled cities like Peftjaubast in Herakleopolis, Nimlot in Hermopolis and Ini in Thebes.

Twenty-Fourth Dynasty

The Nubian kingdom in the south took advantage of Egypt’s division and instability. Before Piye’s campaign in year 20, the previous Nubian king Kashta had already extended his influence to Thebes. He forced Shepenupet, the Divine Adoratrice of Amun and sister of Takelot III, to adopt his daughter Amenirdis as her successor. About 20 years later, around 732 BC, Piye marched north and defeated several local Egyptian rulers: Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, Iuput II of Leontopolis, and Tefnakht of Sais.

Twenty-Fifth Dynasty

Piye established the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and made the defeated rulers provincial governors. He was followed by his brother Shabaka, and then by his sons Shebitku and Taharqa. The Nile Valley empire in this dynasty was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom.

Pharaohs of the dynasty, including Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments across the Nile Valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal. The dynasty ended when its rulers returned to their homeland in Napata. There, at El-Kurru and Nuri, all the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty pharaohs were buried under the first pyramids built in the Nile Valley for hundreds of years.

This led to the rise of the Kingdom of Kush in Napata and Meroe, which lasted until at least the 2nd century AD.

Egypt’s Decline and Conflict with Assyria

By this time, Egypt had lost much of its international influence. Its allies were under Assyrian control. From around 700 BC, war with Assyria was only a matter of time. Assyria had more wood and charcoal to produce iron weapons, while Egypt had a chronic shortage. This gave Assyria an advantage during their invasions of Egypt from 670–663 BC.

During this time, Pharaoh Taharqa and his successor Tantamani faced constant battles with Assyria. In 664 BC, the Assyrians attacked Egypt and sacked Thebes and Memphis. After this, no Kushite ruler ruled Egypt again, starting with Atlanersa.

End of the Third Intermediate Period

Upper Egypt stayed under Taharqa and Tantamani for a while, while Lower Egypt was ruled by the new Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, which were Assyrian client kings, from 664 BC.

In 663 BC, Tantamani invaded Lower Egypt, captured Memphis, and killed Necho I of Sais, who had been loyal to Ashurbanipal. But a large Assyrian army led by Ashurbanipal and Psamtik I, Necho’s son, returned and defeated Tantamani north of Memphis. Thebes was sacked and Tantamani withdrew to Nubia. Assyrian control in Upper Egypt quickly faded.

After that, Thebes surrendered peacefully to Psamtik’s forces in 656 BC. To confirm his authority, Psamtik appointed his daughter as the future Divine Adoratrice of Amun, bringing the priests under his control and effectively uniting Egypt. Atlanersa, Tantamani’s successor, could not attempt to reconquer Egypt. Psamtik secured the southern border at Elephantine and may have sent a campaign to Napata. He also freed himself from Assyrian control while keeping good relations with Ashurbanipal, possibly due to a rebellion in Babylon. This brought stability to Egypt during his 54-year reign from Sais, marking the start of the Late Period.

The Late Period of the Ancient Egyptian kingdom

The Late Period of Egypt was the last phase when native Egyptian pharaohs ruled after the Third Intermediate Period. It began with the 26th Dynasty (Saite Dynasty) founded by Psamtik I and lasted until the Greek conquest. During this period, Egypt was also ruled by the Achaemenid Persians after Cambyses II conquered it in 525 BC. The Late Period lasted from 664 BC to 332 BC, starting after foreign rule by the 25th Nubian Dynasty and a short period of Neo-Assyrian control with Psamtik I initially serving as their vassal. The period ended when Alexander the Great defeated the Persians, and his general Ptolemy I Soter established the Ptolemaic Dynasty, beginning Hellenistic Egypt.

The History

26th Dynasty

This dynasty is also called the Saite Dynasty, because its capital was Sais, and it ruled from 672 to 525 BC. It included six pharaohs. Psamtik I unified Egypt around 656 BC, after the Assyrians sacked Thebes in 663 BC. During this time, canals were built connecting the Nile River to the Red Sea.

Egypt expanded into the Near East, capturing the city of Ashdod around 655 BC. Many archaeological finds in the Levant, including Egyptian objects, inscriptions, and documents, show Egypt’s control and taxation system in the late 7th century BC. Egyptian influence sometimes reached areas near the Euphrates, such as Kimuhu and Quramati, but they retreated after the Battle of Carchemish.

In 570 BC, Amasis II became pharaoh after overthrowing Apries (Hophra). Around 568–567 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon invaded Egypt. At first, the Babylonians were successful but Amasis II’s army eventually repelled them.

Amasis II focused on building relations with the Greek world and annexed Cyprus. To the south, Psamtik II led a large military campaign into Upper Nubia, defeating them. Archaeological evidence also shows an Egyptian garrison at Dorginarti in Lower Nubia.

One of the important contributions of this period is the Brooklyn Papyrus, a medical papyrus that contains remedies for snakebites, combining medical and magical treatments according to the type of snake and symptoms.

Art during this time focused on animal worship and animal mummies. For example, the god Pataikos is depicted with a scarab on his head, human-headed birds on his shoulders, snakes in his hands, standing on crocodiles.

27th Dynasty

The First Achaemenid Period (525–404 BC) began when Cambyses of Persia conquered Egypt at the Battle of Pelusium, turning Egypt into a Persian province (satrapy). Persian rulers, including Cambyses, Xerxes I, and Darius the Great, ruled Egypt as pharaohs through their satraps.

Some Egyptians rebelled against Persian rule, such as Petubastis III (522–520 BC) and possibly Psammetichus IV. Another rebellion by Inaros II (460–454 BC), supported by Athens, also tried to restore Egypt’s independence. Persian satraps during this period included Aryandes, Pherendates, Achaemenes, and Arsames.

28th–30th Dynasties

The 28th Dynasty had only one king, Amyrtaeus of Sais, who successfully rebelled against the Persians and ruled from 404–398 BC.

The 29th Dynasty ruled from Mendes (398–380 BC), and King Hakor was able to repel a Persian invasion.

The 30th Dynasty (380–343 BC) followed the artistic style of the 26th Dynasty. Nectanebo I defeated a Persian attack in 373 BC. His successor, Teos, led a campaign into the Near East but was betrayed by his brother Tjahapimu, who made his son Nectanebo II pharaoh. Nectanebo II became the last native Egyptian ruler, and he was eventually defeated by the Persians.

31st Dynasty

The Second Achaemenid Period (343–332 BC) returned Egypt to Persian control. The pharaohs were Artaxerxes III, Artaxerxes IV, and Darius III, with a short rebellion by Khababash (338–335 BC).

32nd Dynasty

Persian rule ended when Alexander the Great defeated the Achaemenid Empire in 332 BC, and the Persian governor Mazaces surrendered. This marked the beginning of Hellenistic rule in Egypt. Alexander appointed Cleomenes of Naucratis as the overseer (satrap). After Alexander’s death, his generals, the Ptolemies, established the Ptolemaic Kingdom, sometimes called the 33rd Dynasty.

FAQS

What were the Genetics of the Old Kingdom?

A 2025 genetic study sequenced the genome of an Old Kingdom man from Nuwayrat, south of Cairo. Most of his ancestry was North African Neolithic with more than 20% from the eastern Fertile Crescent including Mesopotamia.